The Big Tree: Natural History at Camp Birch Hill. Written by Matt D’Anieri.

One cannot tell the vibrant history of Camp Birch Hill without mentioning the eastern white pine tree. These towering conifers greet us everywhere we walk, from the cabins at lower camp, up to the cafeteria and rec hall, and across the fields to the cabins at upper camp. Each one was carefully planted as a fragile seedling by the first directors of Camp Birch Hill nearly a hundred years ago. Today, they provide us with shade from oppressive summer sun, and shelter from flashes of rain. We play and relax safely under the support of their majestic trunks, setting up webs of hammocks and slacklines to spend hours lounging in the evergreens. Their needles and pollen somehow end up everywhere, giving our bunkmates the shared responsibility of constant cabin upkeep, a gentle reminder that we are indeed living together in the woods. Every morning when we wake up, we need to walk under the canopy to get to breakfast, inevitably bringing their prickly foliage and sweet aroma wherever we go. We appreciate those stubborn needles.

The most sacred ground on camp, where we channel all of our Birch Hill spirit several times per day, is at Cove, our circle of pines in the middle of the fields. It is safe to say that these monarchs of the land have seen millions of magical moments and watched generations of people and families grow up at camp. They exist in a beautiful synergistic relationship, having grown up intentionally spaced together, shielding each other from winter storms in the exposed field. If there were only a few of them in random positions, we would have no way to release our “Yahoo” at the start of each day, which would simply render us powerless and unable to perform the basic functions of a day at camp. Just like a Birch Hill Cup-winning cabin, these pines in Cove are infinitely stronger together than the sum of them as individuals. They share a beautiful story and legacy, as do all the aforementioned rows of pines in the open spaces around camp. But of all the seemingly countless eastern white pine trees that dominate the 106 acres of camp from the waterfront to the forest to the fields, there is one tree that holds a unique story all its own… a pine older, wiser, and far more jaw-dropping in size than its neighbors. Have you seen it?

I am on the Burley Trail, where it hits a low point at the bottom of the hill behind the mini golf course. The trail abruptly rises from there to Cannon Ridge, an open, well-maintained junction where I can see the old Fletcher family graveyard on the left. The Burley Trail continues straight to go behind the cabins on lower camp. The left turn that hooks sharply around the stone fence of the graveyard meanders downhill towards a swampy, less-maintained area. Between these two trails, there is a section of woods that is slightly more thinned out- it is still covered in bushes and small trees eagerly competing for sunlight, but there is just enough space to invite me to descend down the hill through this section. As I bushwhack through young beeches and maples, I begin to see the top of the big tree. My excitement and the downhill sends me crashing through the leaves as I get closer. However, with most of the tree in view now, it would still look very unassuming to someone who does not know what they are looking for. It appears that once I turn the corner around the last stretch of bushes and trees obscuring my view, I will get to four pretty tall pines. Not crazy tall or higher than the surrounding canopy, just about the size of one of the trees on the paths around camp. I can hear the gurgle of nearby Hayes Brook further downhill, and beyond that I can actually hear the occasional car very clearly. I have walked towards Birch Hill Rd, and the setting feels much more ordinary than enchanted.

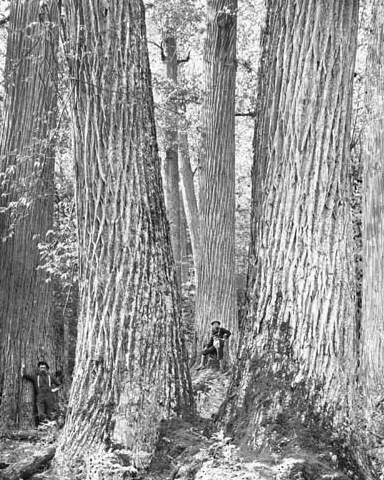

It is not until I get about twenty-five feet from my destination that I finally see the tree in all its glory. I have been to this tree many times now, but I gasp in awe and pause in my tracks with wide eyes just as I did the first time I saw it. Those four large white pines seen from afar? Well… they are actually all part of a single tree trunk. At breast height, the trunk measures just under eighteen feet around. It sits on a steep slope next to a large split boulder that looks like the trunk could have swallowed its other half. Instead of having a symmetrical circular trunk, this one folds and ripples into irregular shapes and bulges. Instead of growing straight up, the pine splits into five large limbs, four of which reach the canopy. And the crazy part is that I can tell that it used to have even more of these limbs! A few sections are hollowed out from where a now dead limb used to extend towards the sky. In so many ways, this tree is unapologetically unique. Through a deep dive into forest ecology and the natural history of New England, we can construct a fascinating story of how this great tree came to be, as well as its priceless contribution to the land here at camp.

Camp Birch Hill is on the land of the Abenaki people. These indigenous communities managed the forests of northern New England and Canada for thousands of years since the last ice age, nurturing the landscape and allowing massive trees to grow for hundreds of years. Colonizers arriving from Europe held the belief that land ownership was conditional on cultivating it and using it for its resources. After many of Europe’s timber resources had been exhausted, Pinus strobus, the scientific name for the eastern white pine, became heavily sought after by the British, who used its tall trunks for the masts of their ships. Historical accounts of old-growth forests (forests that had previously never been cut for timber) have reported finding white pines up to 270 feet tall! The largest of these were all cut down, mostly in the 1700s and 1800s. By this time, British settlers were not just harvesting pines, but they were cutting down entire forests, indiscriminately of the species of tree, in order to use the land for agriculture. It is estimated that 80% of New England’s forests were cleared for farming. This is how the Fletcher family, who lived at Birch Hill in the 1800s, and whose names are carved into gravestones at Cannon Ridge, used the land for several generations.

It may be hard to believe, but the forest around Birch Hill that we see today used to be rolling, open fields, grazed by sheep and cows as far as the eye could see. Have you ever walked in the woods at camp, or anywhere in New England for that matter, and come across a stone fence, wondering why something like that would stretch through a dense forest? Well, those fences were all built when the forest was cleared, to serve as property markers and keep livestock from venturing away. In some areas of their properties, farmers might spare one tree from clearcutting, allowing it to grow in an open field either as a property marker or as a source of shade for their grazing animals. This is where the story of our special tree begins.

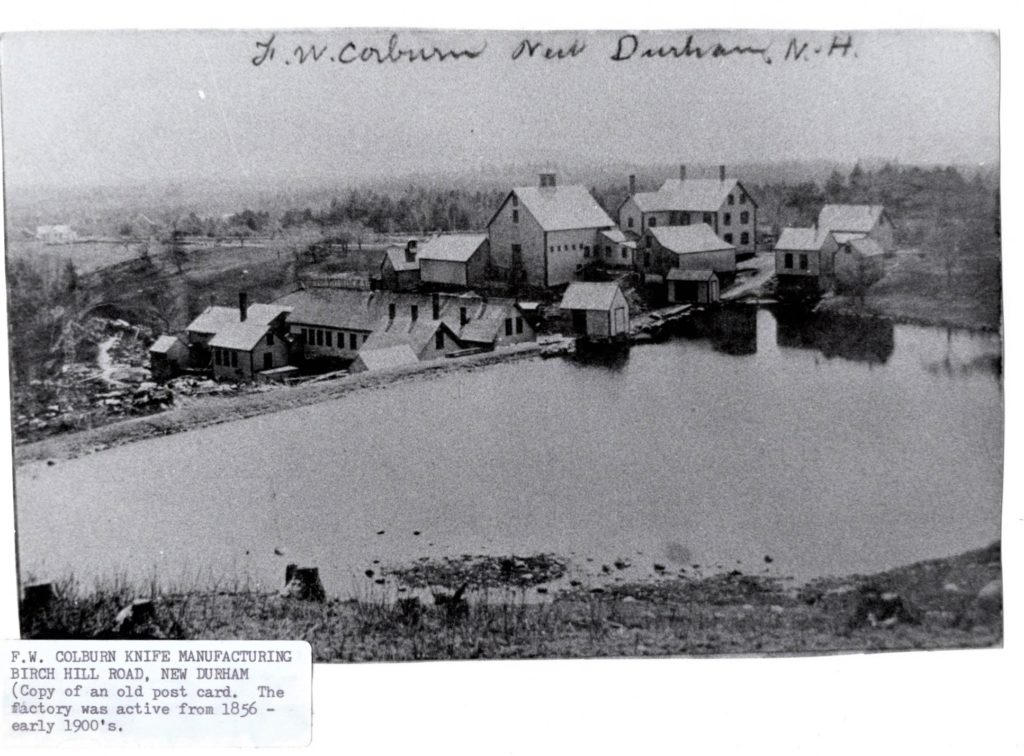

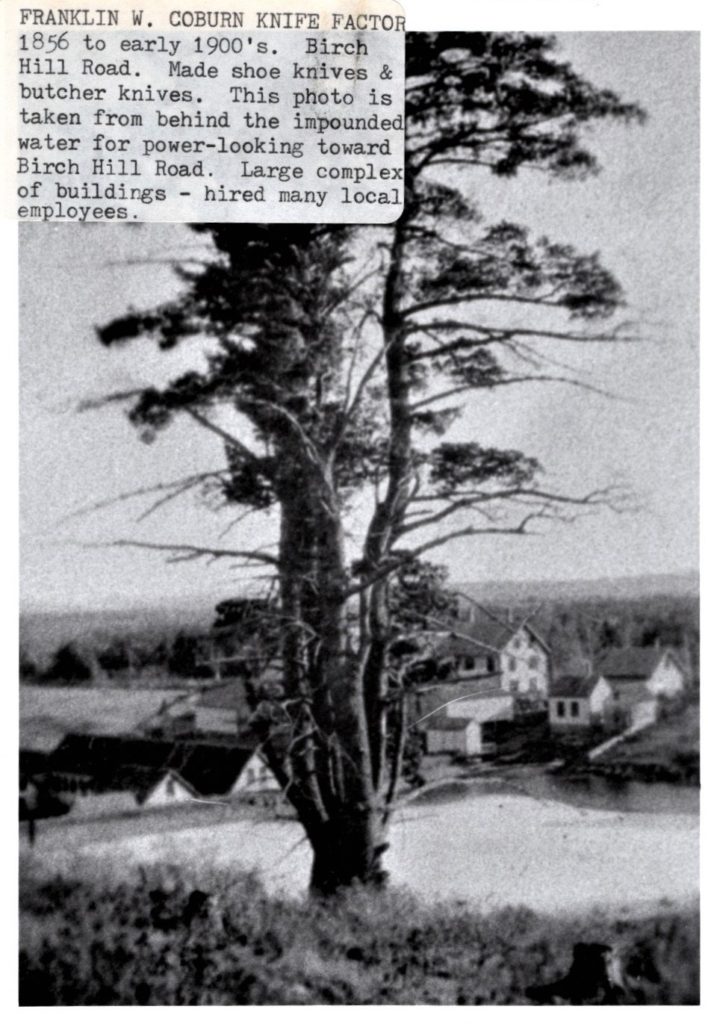

When driving up Birch Hill Road to camp, just before seeing the Birch Hill logo and making that exhilarating right turn down our dirt road, you may see another old family graveyard followed by a compound of several very old, tall wooden buildings. Behind these buildings, the land drops off into a swampy area, directly across Hayes Brook from our giant tree. This is the site of the Coburn family knife factory, which in its heyday distributed knives all over the country. New Durham’s town historian recovered an old photo, which dates back to sometime in the late 1800s, depicting an open, sweeping view from camp property, looking downhill towards the knife factory, where a large pool held water dammed up from Hayes Brook for the factory’s hydroelectric power. Even back then, in the middle of an open field, the white pine tree and its distinct bunch of several broad limbs looms over the otherwise empty hillside. This is a tree far older than any other tree at camp. Over centuries it has silently witnessed the growth and development of America.

Photo curtesy of New Durham, NH Historical Society, Cathy Orlowicz.

Photo curtesy of the New Durham, NH Historical Society, Cathy Orlowicz

The environmental processes that a tree like this undergoes are even more fascinating than the rich pastoral history surrounding it. In a dense, dark forest, young trees grow skinny and straight up, reaching their lead bud directly towards the canopy as they compete for sunlight with close-by trees. However, when the rest of the forest is cut down for agriculture, the remaining tree grows up in an open field. It has an abundance of sunshine all to itself with no competition from neighbors. This allows the tree to spread its limbs in every direction, which in turn provides more shade for the livestock that it was saved to serve. This is why the pine at camp sports such an enormous trunk. Do not be mistaken by the multitude of limbs growing from it- tree experts have visited the tree, inspected it, and confirmed that it indeed sprouted from a single tree! The land use for the Coburn knife factory may have also played a role in its growth, as their dam on Hayes Brook would have caused more water to permeate into the soil on the hillside and raised the water table, so that the tree could get more water and nutrients to grow big. After the peak of agriculture and forest clearing in New England from 1830-1880, small farms were abandoned for larger operations and more fertile soil further west. Slowly but surely, the extremely resilient eastern forests returned to take over the landscape in a process known as “old field ecological succession”. First, perennial flowers, whose seeds had been buried in the rocky soil, sprouted up in the fields, followed by shrubs, then pines and hemlocks, emerging to build a young forest over the course of a few decades. As the forest matured, hickories, maples, beeches, oaks, and yes, birches, among many other species, returned and grew into many of the tall, mature trees that we see in the woods at camp today. In some cases, there were even more rounds of logging, and this great tree survived again. A small portion of the woods at camp were logged a little over ten years ago in order to begin building our trail system, so in some places on camp we can witness ecological succession in real time!

While the lone white pine tree has a very unique history here at Camp Birch Hill, we can look in our own nearby forests and find other trees that seem to emit a similar sense of character, wisdom, and history. However, it is only relatively recently that such trees have been recognized as a positive feature of a forest. When landowners noticed how quickly the forest grew back from clearcut fields, they realized that they could utilize this rapid growth for timber resources. Trees would grow tall and straight in dense stands, but not underneath the older pasture trees, whose spreading limbs would prevent trees from getting sunlight. These trees, with their irregular and gnarled trunks, were not any good for timber, and were seen as taking away forest space and resources from young, profitable trees. Foresters likened this to lone wolves preying on livestock, and recommended that they be dealt with in a similar fashion. Out of this was borne the colloquial New England term “wolf tree”. This term does not denote any specific species, but rather any tree that is older than its surrounding forest, grew up in a lot of sunlight, and spread its limbs wide as a result.

Today, the few wolf trees that were not cut by foresters provide an impressive list of ecosystem services. They tend to be much stronger seed producers than the younger trees around them, and their age and shape provide more complexity and diversity to the structure of a forest that would otherwise have very uniform trees of nearly all the same age. Wolf trees are also important to animals that call the forest their home. Birds and many other small animals spend more time in the extensive limbs of wolf trees than in other trees. They provide opportunities for larger mammals as well, whose scat and tracks can commonly be found at the base of these massive trees. When lower limbs in these trees die and rot, their hollows can serve as homes for top predators of the forest, including bears. If you come across a wolf tree in the winter, look for prints in the snow just to see how much wildlife activity revolves around them. Wolf trees serve as a sort of town center for forest dwellers. For this reason, many naturalists consider wolf trees to be keystone structures of the forest, since their value to their ecosystem is disproportionately high relative to their abundance.

All of this knowledge about the origin and history of the magnificent white pine at camp makes it even more precious to us, and makes the land at camp feel all the more special. For this reason, we plan to invest our care in the preservation of this tree, so that it may inspire awe and imagination among Birch Hillers and serve the ecosystem at camp for generations to come. As mentioned earlier, I can tell that some of its lower limbs have died and hollowed out. The tree is generally in good health, but its biggest threat is the shade of its direct neighboring trees, who may prevent its lower limbs from getting the sunlight they need. This is a common problem for wolf trees in the region, and we plan to employ thoughtful forest management practices to maintain the surrounding trees so that the ancient pine can continue receiving sufficient sunlight. Equally important is raising awareness of these increasingly rare gems of our forests. Not only do such trees serve as relics of pastoral America and ecological keystone structures, but their presence is powerful enough to inspire in future generations a sense of stewardship and love for the land! If a place as beautiful as Camp Birch Hill has taught you nothing else, we hope that it has instilled a love for nature and the outdoors, and that you will spread that passion to your community!

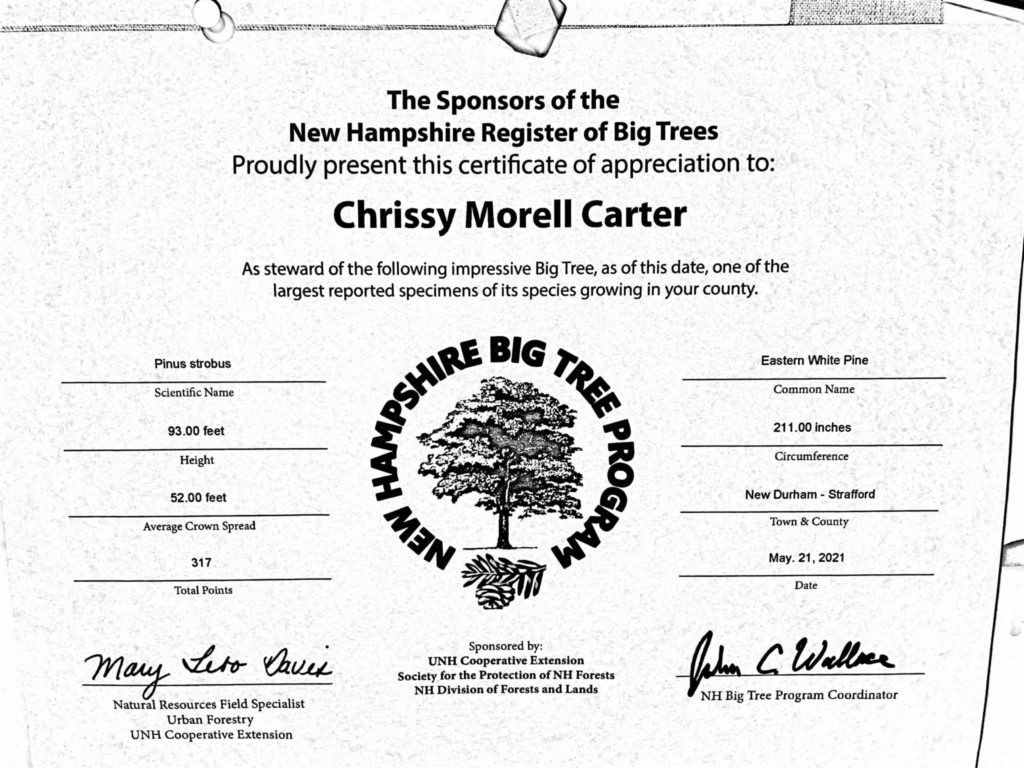

We encourage all of you in our Birch Hill family to go out and look for big trees near you! This pursuit has become easier in recent years, with various organizations publishing information on the “champion trees” in each state. There is even a point system, which factors in a tree’s circumference, height, and crown spread to make a total score for any given tree. The pine here at camp scored just a few points away from being a county champion for Strafford County, New Hampshire! But there are always more big trees out there for us to find. At the bottom of this article, you can find links to information on New Hampshire’s list of champion trees, as well as Massachusetts’ legacy tree program. Additionally, American forests has compiled a registry of national champion trees, that is, the biggest trees of each species in America! Are there any big trees near you? See if there is a big tree list in your region. Go out and look for the most picturesque wolf trees or the most towering tall trees you can find! We cannot wait to take you to this special white pine tree at camp next summer, but until then, happy tree hunting!

The vertical height (VH) measured with the laser is 93′. The circumference (CBH), as measured by Sam Stoddard and Charlie Tatham, is 211″. The total points for this tree (as of this posting) is 318 and close to being a county champion.

National Register of Champion Trees